Enduring Legacy.

by Tim Palmer [Pick up from story in the email.]

A native of Pennsylvania, my first knowledge of the Stanislaus River came in Louisiana, from Alexander Gaguine, of Washington D.C.-gone–to-California. Out for a field trip in the Atchafalaya Swamp while attending a national river conference nearby, I was impressed that Alexander swam much of the route while the rest of us paddled in canoes—a wall of aluminum separating us from the alligators. This new friend of mine seemed fearless. I was impressed.

Years later when I recounted that day, Alexander responded, “Hey, I never knew there were alligators there!“

More important than this happily inconsequential oversight on his part, I took notice at what appeared to be the same level of moxie when—after we returned from the swamp—Alexander told me, “The Stanislaus River is scheduled to be flooded, and we’re planning to stop them, but if we don’t, we intend to make this the most visible loss of a wild river in history.“ Or something to that effect.

I was already engaged in campaigns to protect other rivers all over the country during the fiercely embattled days of the big-dam-building-era. When I met Alexander, I was writing a bittersweet book about wild rivers that would never be seen again because the floodgates were slated to shut on dams at gems such as the Little Tennessee, Applegate, Delaware, Gila, and South Platte. “If you’re writing about threatened rivers,” Alexander said, giving me no out, “you’ve got to include the Stanislaus.”

“Okay,” I thought, “I’m in.” Making river beauty visible was my game as a photographer, and telling people about rivers’ importance is what I wanted to do for a living as a journalist, or author, or whatever might be in store for the next chapter of my life.

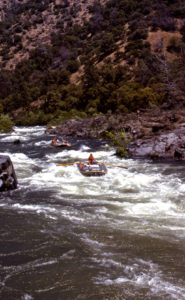

Then I met Mark Dubois, and some of you might get the drift of how this story is going to go. Now there was no doubt that I needed to include the Stanislaus in my nationwide photo tour of endangered rivers. When I arrived, autumn of the drought year, 1977, I hiked into the canyon and knew, right away, that it was the most beautiful place that I might never have the privilege of seeing again.

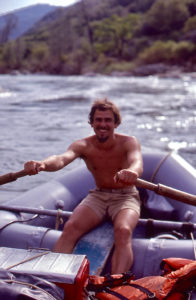

When New Melones Reservoir waters began to rise, two years later, and Mark hid in the canyon and chained himself to a rock in protest, I scheduled three weeks off my job as an environmental planner, crammed a sleeping bag and a bunch of cameras and notebooks into my backpack, and flew to San Francisco. I hitchhiked to Angels Camp and the OARS base, floated the Stanislaus with Mark, and Alexander, and Catherine Fox, and Richard Roos-Collins, and others of Friends of the River, and rushed three stories off to national magazines about the unconscionable flooding of that remarkable place.

Pressed by Governor Jerry Brown, the Army Corps released water from the rising reservoir, sparing the life of our pal Mark, and the snowmelt receded, buying us another year to save our precious river. I now say “our,” as I, too, had adopted that canyon as home, and committed myself not only to writing about it, but to doing everything I could to spare the dark and gloomy fate that awaited it if nothing were done.

Back in Pennsylvania, I persuaded my boss to give me another three weeks off, without pay this time, and I returned to California to lead a team of enthusiastic volunteers writing a report aiming to bolster the campaign for adding the Stanislaus to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system—a program that I knew well from my planning work.

We failed to keep that possibility alive by one committee vote in Congress. I left my job then, for good, and packed up my van (which I proceeded to live in for the next 22 years), and moved to California to write a book about Friends of the River’s efforts while there was still time to possibly turn the tide. But the Stanislaus was flooded by the dam the next year. And for most years ever since.

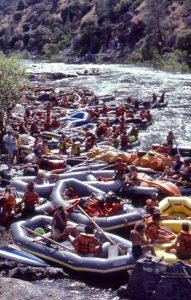

Nothing has ever been quite the same. Certainly not for me, nor for hundreds of people who were dedicated to doing whatever they could to save our whitewater Eden. The place is gone. Picking up the pieces constructively, Friends of the River went on to work for protection of all California rivers, and to grow, flourish, and persevere. Dozens of the FOR activists and staff went on to illustrious careers working for river protection or other worthy causes. But through it all, the flooded Stanislaus left an empty place in the hearts of many.

I went on to write about other rivers, and the threats that they faced, and with my perspective of historical journalism, I soon realized that the Stanislaus was not just a loss without replacement, but one that represented a profoundly significant turning point. A few other smaller dams have been built since then, but the Stanislaus was the last dam-fight waged at the epic scale in America and lost. Those who fought against that dam turned a corner in the environmental history of our nation. Of course we were too close to see that at the time.

Post-Stanislaus efforts were immediately focused on the Tuolumne, where a dam and diversion plan was stopped with National Wild and Scenic designation in 1984. Friends of the River, sometimes led by its essential allies, stopped unnecessary and destructive dam proposals on the Kings, Merced, Kern, North Fork American, and South Yuba. Now they continue to fight for the McCloud, the San Joaquin, and other streams within a megalith of water-based geography, policy, and politics—which no one even in our darkest days ever imagined could get so bad as the Trump administration.

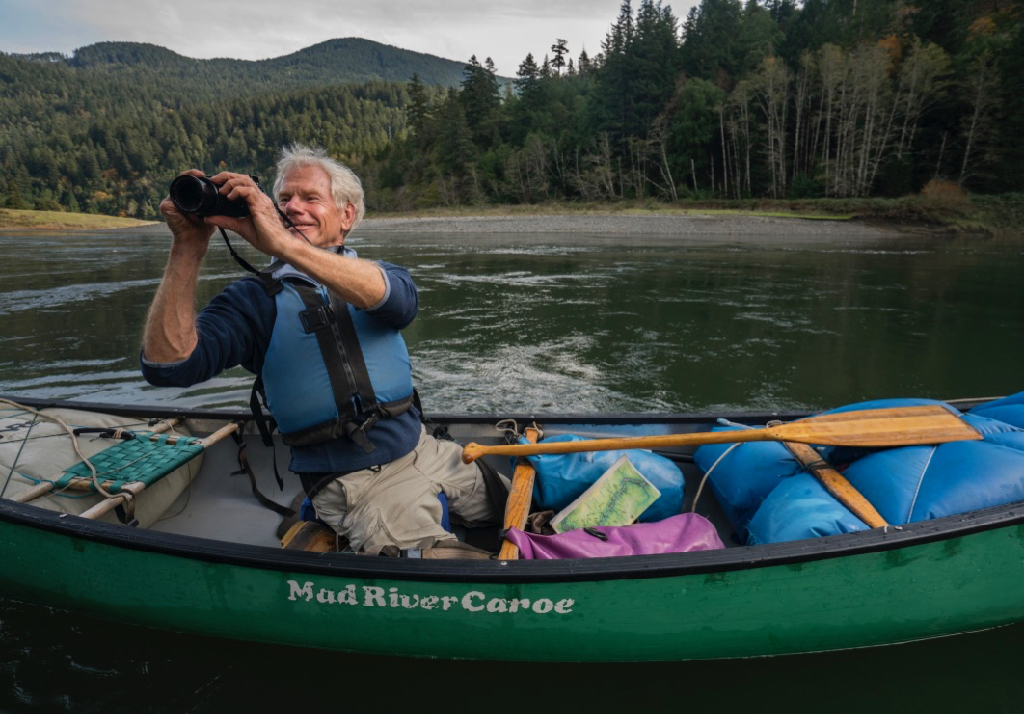

My career and passion for wild rivers and their protection took me from Pennsylvania to the Stanislaus with hopes of preventing the river’s loss but also with resolve that it’s beauty would be remembered. Little did I—or anyone then—know that in the long arc of history, this would be the place where the world would change. Other battles will continue, and new ones—like at the McCloud—will surface. And the threats are so much larger today, with global warming and the droughts, fires, floods, and rising sea level it brings, including ever-greater demands on all our streams. But so long as Friends of the River is there, never will a California river as brilliant and beloved as the Stanislaus be lost again.

You can still find Stanislaus: the Struggle for a River, online. See Tim’s other work at www.timpalmer.org.